TEHRAN — Water transfer won’t restore Lake Urmia, Hedayat Fahimi, an official with the Ministry of Energy has said, noting that promoting sustainable agriculture is the way to save the lake. Lake Urmia, located in northwestern Iran, used to be the largest salt-water lake in the Middle East and a home to flamingos, pelicans, egrets […]

TEHRAN — Water transfer won’t restore Lake Urmia, Hedayat Fahimi, an official with the Ministry of Energy has said, noting that promoting sustainable agriculture is the way to save the lake.

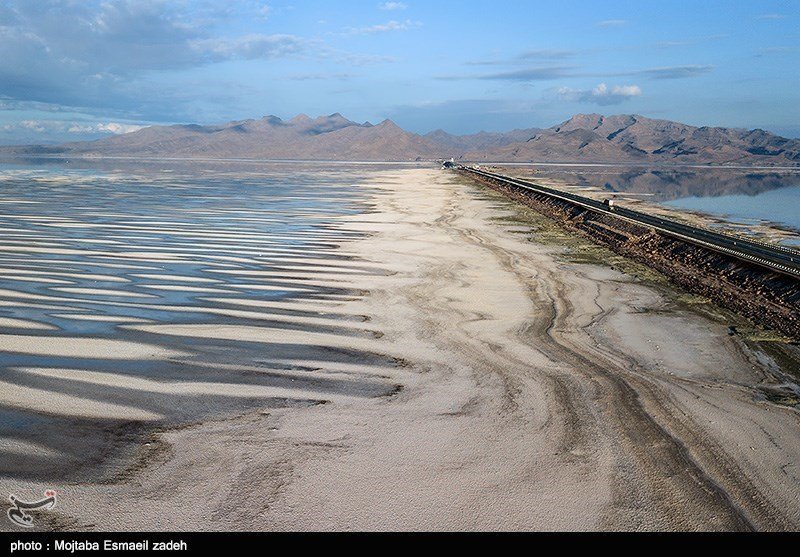

Lake Urmia, located in northwestern Iran, used to be the largest salt-water lake in the Middle East and a home to flamingos, pelicans, egrets and ducks and attracted hundreds of tourist every year who had taken a trip to take advantage of the therapeutic properties of the lake.

However, the lake started to shrink in 1990s. The volume of water which measured at 30 billion cubic meters dramatically decreased to half a billion cubic meters in 2013 and again rose to 2.5 billion cubic meters in 2017 and accordingly lake surface area of 5,000 square kilometers in 1997 shrunk to one tenth of that to 500 square kilometers in 2013.

And now, as per the data published on Iran Environment and Wildlife Watch website on April 8, the lake is stretching over some 2,200 square kilometers of land area and the volume of water is measured at some 2 billion cubic meters. Water transfers — massive engineering projects that divert water from rivers with perceived surpluses to those with shortages — have been promoted as a solution worldwide.

In order to revive the lake many believe that the only solution left is water transfer which is a man-made conveyance schemes which move water from one river basin where it is available, to another basin where water is less available or could be utilized better for human development.

However, as Fahimi explained, the lake won’t be restored with water transfer and managing the water use and sustainable agricultural practices are the route to save the lake.

Agriculture is both a cause and a victim of water scarcity. But Fahimi noted that transferring water would only lead to unexpected increase in water demand and encourage unsustainable water use in all sectors.

Implementing water-demand management policies can improve the supply-demand balance in water-stressed regions, he suggested.

Moreover, he said, “transferring water from other countries would act against our national interest.” “For one, once we grow dependent upon water transferred to our country the other countries might push up the prices, won’t let the water flow into transboundary wetlands and even ignore the water right of the downstream wetlands and rivers.”

In an article published in Hamshahri Persian language daily newspaper on April 9, Hossein Akhani, botanist and environmentalist, said that “there are only certain blood types that can be used should anyone need a transfusion and there are factors determining the right type of blood for each person, likewise we cannot transfer any water from anywhere to quench the Lake Urmia.”

Each basin has its distinguished physical and biological characteristics and inter-basin water transfer can have unpredictable effects on the lake ecosystem such as endangering the biodiversity of the region, Akhani said, adding that the money, earmarked for water transfer schemes, can be spent on reforming irrigation patterns as well as agricultural practices and creating jobs other than farming.